Introduction

The concept of using the wind as an energy source has been around for thousands of years. Over this time period wind has been used for applications as massive as propelling ships across the oceans to grinding grain into flour. In 1890, only eight years after Edison founded the Edison Electric Illuminating Company, Americans began to use windmills to generate electricity for their homes and businesses. Now nearly 130 years later, in the United States alone, wind energy is responsible for powering over 28 million homes, with an installed capacity of over 96 gigawatts according to the U.S. Department of Energy [1]. In their 2015 report titled “Wind Vision: A New Era for Wind Power in the United States” the U.S. Department of energy went on to project that by the year 2050 wind power could account for up to 35 percent of all U.S. energy demands [2]. With all of these factors in mind, it is no wonder that wind turbine technology has advanced so rapidly over the past 50 years with the modern three-blade horizontal wind turbine capable of achieving up to 50 percent energy conversion efficiency [3].

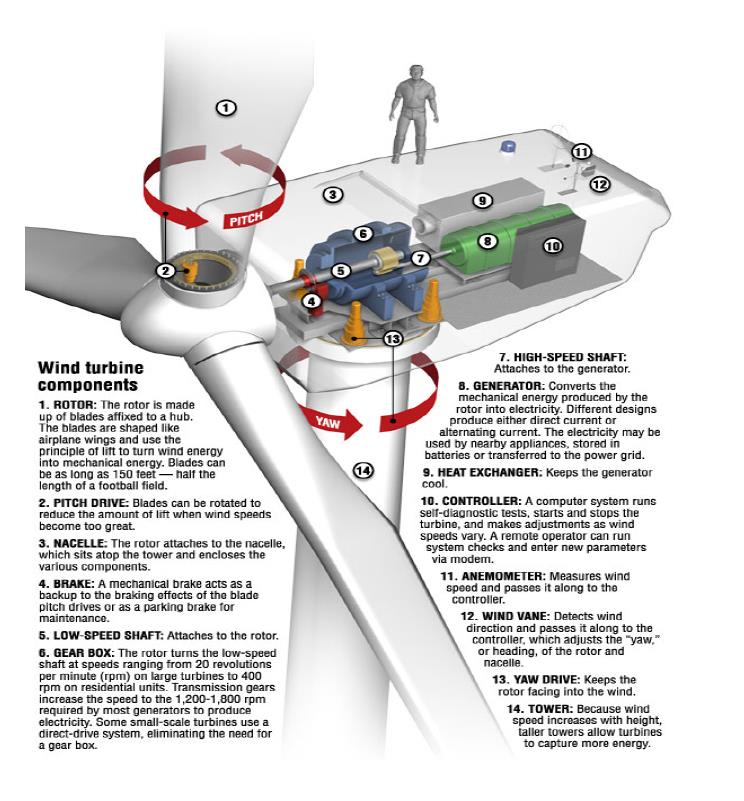

These modern wind turbines function on the same basic principles as an airplane wing, utilizing their curved shape to produce a pressure differential on either side of the blade as the wind passes over it. Additionally, just as an airplane wing can generate different amounts of lift depending on the angle of the wing, so to can the wind turbine blade generate different rotational speeds as the pitch of the blade is varied. This is a critical factor in ensuring that the blades maintain a rotation velocity required for structural stability, in laymen’s terms if the pitch is not controlled the windmill can spin out of control and possibly explode. Figure 1 below, reproduced from an article published in Energies titled “Wind Turbine Blade Design,” (taken initially from www.desmoinesregister.com) shows among other things that both the pitch and the yaw of the wind turbine can be actively controlled to ensure continual safe operation [3].

Figure 1: Typical configuration of a modern large-scale wind turbine, showing active pitch and yaw control [3].

Windspeed measurement with LiDAR

While in the figure above the windspeed was shown to be measured with a mechanical anemometer and wind vane located on top of the generator tower, over the past ten years these devices have been shown to be slow to report extreme weather changes. The image below in figure 2, is just one example where a storm off the Atlantic caused wind speeds to reach 160 miles per hour in Ardrossan, Scotland, resulting in the turbine exploding [4]. One approach to solving this problem that is starting to be implemented around the world installs a network of single frequency Doppler LiDAR sensors around the wind farm allowing for much higher accuracy of wind speed from all directions. While it is important to note that due to the turbidity of wind flow through a wind farm it is inevitable that wind speed will evolve between the LiDAR sensor and the wind turbine itself, researchers such as Simley and Pao at the University of Colorado, have been able to develop highly accurate models for predicting such effects [5]. In their recent review article published by National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), they went on to explain that when this methodology is applied to a radially scanning LiDAR sensor mounted atop the turbine, it will produce the optimal results at a scanning distance of approximately 150m away from the turbine.

Figure 2: Wind turbine in Scotland exploding after failing to detect extreme wind.

Doppler LiDAR, which we discussed in great detail in a previous white paper titled “Single Frequency Fiber Lasers for Doppler LiDAR,” measures velocity by measuring the Doppler shift of the scattered laser light compared to that of the transmitted signal [6]. In that same ar

SHIPS TODAY

SHIPS TODAY